| World Journal of Nephrology and Urology, ISSN 1927-1239 print, 1927-1247 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Nephrol Urol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.wjnu.org |

Case Report

Volume 3, Number 1, March 2014, pages 49-53

The Heterogeneity and Controversy of C1q Nephropathy: A Report of Two Cases and Review of the Literature

Sufia Husaina, b, Hala Kfourya

aDepartment of Pathology, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh 11461, Saudi Arabia

bCorresponding author: Sufia Husain, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, King Khalid University Hospital, King Saud University, PO Box 2925-11461, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript accepted for publication February 20, 2014

Short title: C1q Nephropathy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjnu148w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

C1q is an uncommon, controversial and under-recognized entity. There is disagreement regarding whether it is an established disease or just part of the spectrum of minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. C1q nephropathy is diagnosed solely by kidney biopsy. We report two cases of C1q nephropathy, one in a 39-year-old man and the other in an 8-year-old boy. Our two cases highlight the variable nature of this disease. In this article, we present our cases, review the criteria for diagnosis and highlight the heterogeneous nature of this disease in terms of clinical presentation, renal biopsy and variable outcomes. We also discuss the postulated etiopathogenetic mechanisms and note the reported associations.

Keywords: C1q nephropathy; Kidney biopsy; Minimal change disease; Focal segmental glomerular sclerosis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The C1q nephropathy (C1qN) pattern was first described in 1982 [1]. By 1985, Jennette and Hipp defined the criteria for the diagnosis of this condition [2, 3]. The diagnosis is determined solely by kidney biopsy. The diagnostic criteria include the following: 1) diffuse, dominant/co-dominant C1q deposition in the glomerular mesangium on immunofluorescence (IF), with a minimum staining intensity of 2 on a scale of 0 to 4, 2) corresponding electron-dense deposits in the mesangium and/or the paramesangium on electron microscopy (EM) and 3) absence of any clinical or serological evidence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Since type I membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis can also exhibit strong C1q staining, it has been added as an exclusion criterion.

C1qN commonly presents as steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) in children and young adults. The histological picture is variable and ranges from glomeruli with normal appearance to mesangial proliferation to segmental glomerular sclerosis. C1qN lies in the spectrum between minimal change disease (MCD) and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis (FSGS). We present two cases of C1qN identified in Saudi Arabia, highlight the heterogeneity of this disease and review the literature.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Case 1

A 39-year-old non-diabetic, normotensive man presented with mild generalized swelling without history of recent or past infection. Laboratory tests revealed sub-nephrotic range proteinuria (0.36 g/day) and microscopic hematuria. Serum values of albumin (37.0 g/L), creatinine (67 µmol/L), complements (C3: 1.21 g/L and C4: 0.203 g/L) and urea (3.0 mmol/L) were within normal limits.

Case 2

An 8-year-old boy with history of nephrotic syndrome since 2 years of age presented with resistance to treatment. Laboratory tests indicated presence of nephrotic range proteinuria (25.98 g/day). Serum albumin was low (20.0 g/L). Serum creatinine (32 µmol/L) and serum urea (2.0 mmol/L) were within normal limits. There was no hematuria.

Anti-streptolysin O titer, anti-nuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA, hepatitis B surface antigen, HCV antibody and anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies were negative in both patients. A renal biopsy was performed in both patients.

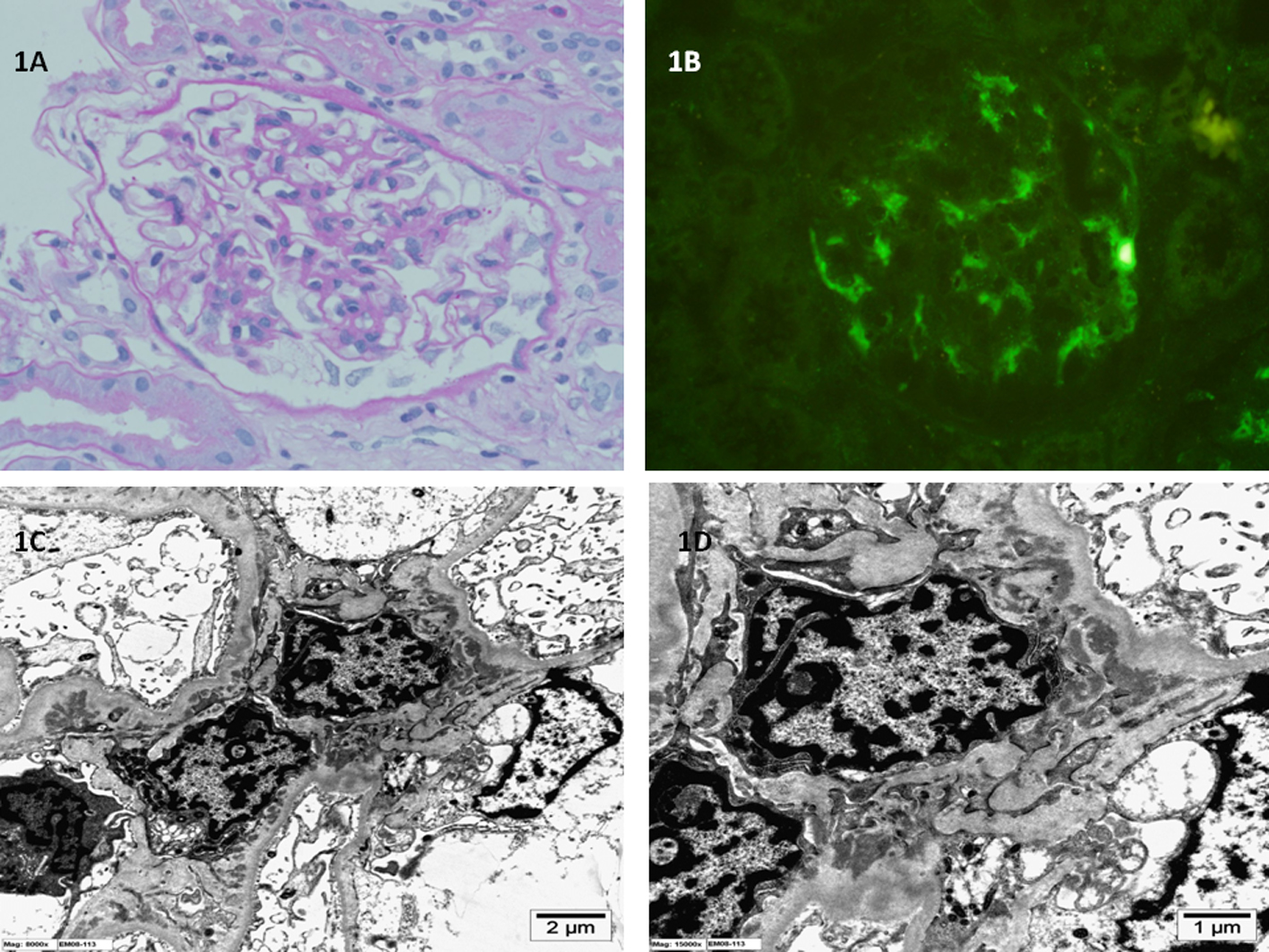

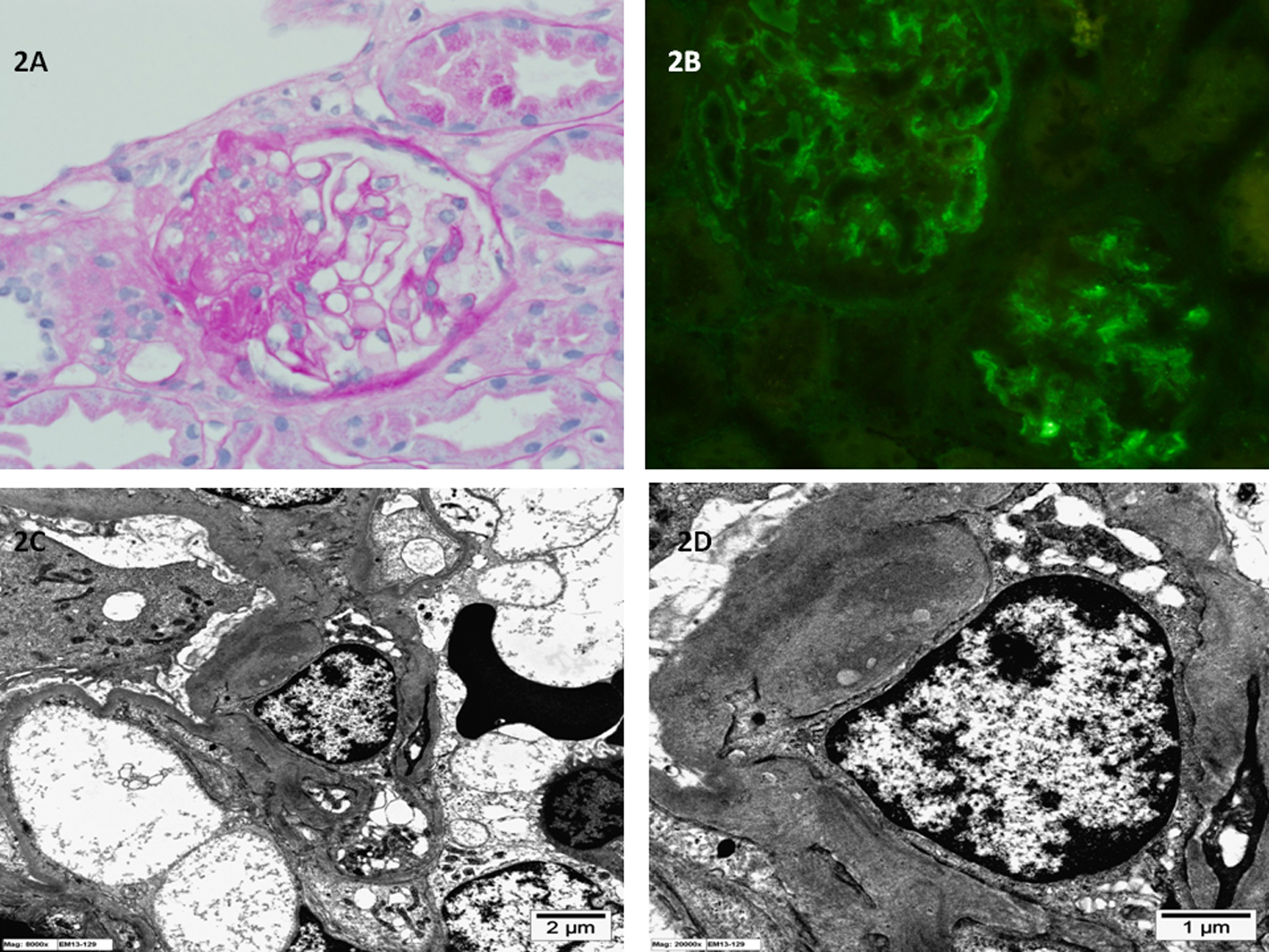

The tissue samples obtained were processed for light microscopy, IF (IgA, IgG, IgM, C3, C1q, fibrinogen and albumin) and EM. Case 1 biopsy showed diffuse mesangial proliferation and matrix expansion with no sclerosis (Fig. 1). Case 2 biopsy showed segmental sclerosis in about 30% of the glomeruli examined and minimal mesangial proliferation (Fig. 2). Neither showed any extracapillary or endocapillary proliferation. IF showed dominant diffuse granular mesangial staining with C1q in biopsy samples from both patients. In case 1, IgG, IgM and C3 mesangial staining were less intense, whereas IgA was negative. In case 2, IgM and IgG were weakly positive and the remaining reactants were negative. EM demonstrated few electron-dense deposits in the mesangium with patchy effacement of the podocytes in both cases; however, the effacement was more widespread in case 2. The glomerular basement membrane was of normal thickness. No tubule-reticular inclusions were identified in either case. C1qN was diagnosed after examination of biopsy specimens from both patients.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (A) Light microscopy of kidney biopsy specimen shows mild mesangial proliferation and mesangial matrix expansion (periodic acid-Schiff stain; original magnification × 400). (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy of kidney biopsy specimen shows global mesangial staining with complement C1q (anti-C1q antibody immunofluorescence; original magnification × 400). (C, D) Electron microscopy of kidney biopsy specimen shows electron dense immune deposits in the glomerular mesangium with extension into the paramesangium (uranyl acetate, lead citrate stain; original magnification × 8,000 and × 15,000 respectively). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. (A) Light microscopy of kidney biopsy specimen shows segmental sclerosis and the glomerular, basement membrane is of normal thickness (periodic acid-Schiff stain; original magnification × 400). (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy of kidney biopsy specimen shows global mesangial staining with complement C1q (anti-C1q antibody immunofluorescence; original magnification × 400). (C, D) Electron microscopy of kidney biopsy specimen shows electron dense immune deposits in the glomerular mesangium (uranyl acetate, lead citrate stain; original magnification × 8,000 and × 20,000 respectively). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

C1qN is characterized by the presence of a dominant or co-dominant deposition of C1q in the mesangium as evidenced on IF and EM, in the absence of any clinical or serological evidence of SLE. Furthermore, absence of a membranoproliferative pattern and hypocomplementemia has been added to the diagnostic criteria [2-4]. The extent of effacement of the podocytes correlates with the degree of proteinuria. Tubuloreticular inclusion bodies are typically absent. The diagnosis of C1qN, similar to IgA nephropathy, is primarily based on the presence of a dominant/co-dominant reactant on IF with corresponding deposits on EM. It is an under-reported diagnosis since many institutes do not routinely perform C1q staining for IF examination of kidney biopsy specimens.

The global incidence of C1qN in the biopsied pediatric population ranges from 1.9% to 6.6% [5]. The incidence in children biopsied for SRNS is 16% [6]. The global prevalence of C1qN ranges from 0.21% to 4% [2, 3, 7, 8]. The prevalence in our hospital has been 0.40% from 2009 to 2013.

Clinically, C1qN tends to occur in children; however, the age range can vary [7]. In the cases reported herein, one patient was an 8-year-old boy and the other was a 39-year-old man. C1qN commonly presents as relapsing or SRNS. It can also present as sub-nephrotic proteinuria, microhematuria or chronic renal disease [9, 10].

There is significant heterogeneity in the findings of light microscopy with a wide spectrum of histological patterns, ranging from no glomerular alterations to focal or diffuse mesangial proliferation to focal segmental sclerosis [8]. Additionally, proliferative glomerulonephritis can occur rarely [8].

C1qN has been divided into two subsets: 1) podocytopathic type with podocyte effacement, proteinuria and an MCD to FSGS histology; and 2) immune complex-mediated type with hematuria or chronic kidney disease and focal to diffuse proliferative disease on histology [8]. Both of our cases were classified as podocytopathic type.

The etiopathogenesis of C1qN is not clear. C1q is produced mainly by antigen-presenting cells such as monocytes and macrophages, and its production is regulated by immune complexes, interferon gamma, lipopolysaccharides and corticosteroids [11, 12]. C1q is the first complement of the classical pathway. The complement cascade is activated by the binding of C1q to the Fc receptors on IgG. Once C1q is activated, the complement pathway is triggered, resulting in the formation of membrane attack complex.

C1qN is an idiopathic disease. Multiple mechanisms have been suggested for C1q deposition in mesangial cells: 1) the passage of plasma proteins in the glomerulus leads to non-specific entrapment of these immunoglobulins in the mesangium and the C1q then binds to Fc receptors of these trapped immunoglobulins; 2) immune complex formation with C1q; 3) C1q directly binds to receptors on the mesangial cells; and 4) increased synthesis of C1q by the macrophages triggered by inflammatory cytokines [5, 13].

C1qN has been reported in association with Bartter syndrome [14], Gitelman syndrome [15] and in a case of chromosome 13 deletion with retinoblastoma [16]. C1qN development in early childhood was also reported in two siblings [17]. Collectively, these findings suggest the presence of genetic associations. However, no genetic testing was performed in our patients.

It may be argued that when other immunoglobulins are also positive on IF, the pathology actually involves seronegative lupus nephritis that ultimately becomes overt. Jones and Magil and Sharman et al reported such non-systemic mesangiopathic glomerulonephritis without progression to overt lupus nephritis [1, 18]. Therefore, the term seronegative lupus nephritis is not useful. On the contrary, the term is confusing and can cause the patient considerable anxiety. In such cases, a diagnosis of C1qN is more appropriate. Furthermore, circulating C1q antibody, typically present in SLE, is absent in C1qN [19, 20]. C1qN should also be distinguished from IgA nephropathy, in which IgA is the dominant stain instead of C1q. C1qN can also be confused with FSGS, but electron-dense immune deposits are very rare in a simple case of FSGS, vis-a-vis the characteristic deposits in the mesangium of a patient with C1qN.

The treatment of C1qN involves combinations of corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors and alkylating agents. Analysis of the published literature on C1qN treatment in pediatric patients showed that 96% of patients were treated with corticosteroids, of which 66% had partial response, 30% were steroid-resistant and 14% progressed to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) [5]. Patients with nephrotic syndrome and MCD histology responded well to treatment and had good prognosis, while patients with FSGS morphology showed poor outcome, with almost 30% progressing to ESKD. Kersnik et al and Vizjak et al reported similar findings [8, 9]. Patients with nephrotic syndrome fared poorly compared to those without nephrotic syndrome [21]. Consistent with these findings, case 1 had only mild mesangial proliferation and responded well to corticosteroid treatment, currently being in complete remission. Case 2 had FSGS histology and showed poor response to cyclosporine combined with immunosuppressive therapy, currently being in partial remission. Therefore, the management and prognosis of C1qN is based not on the deposition of C1q but on the clinical picture, the biopsy findings on light microscopy, and the status of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Perhaps this is why the status of C1qN as an established disease is controversial.

In summary, we report the cases of a child and an adult with C1qN with variable presentation, features and prognosis. We recommend that every relapsing or SRNS patient undergo kidney biopsy and that C1q IF staining be routinely performed in examinations of all kidney biopsy specimens. Moreover, we also consider that C1qN should be part of the differential diagnosis of proteinuria. Although C1qN is a controversial diagnosis and more studies are needed for this disease to become universally established and adopted, we suggest that C1qN be classified as a separate clinicopathological entity, awaiting further study outcomes.

Grant Support

There is no support or funding for this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest with this manuscript.

| References | ▴Top |

- Jones E, Magil A. Nonsystemic mesangiopathic glomerulonephritis with "full house" immunofluorescence. Pathological and clinical observation in five patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;78(1):29-34.

pubmed - Jennette JC, Hipp CG. C1q nephropathy: a distinct pathologic entity usually causing nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1985;6(2):103-110.

pubmed - Jennette JC, Hipp CG. Immunohistopathologic evaluation of C1q in 800 renal biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83(4):415-420.

pubmed - Markowitz GS, Schwimmer JA, Stokes MB, Nasr S, Seigle RL, Valeri AM, D'Agati VD. C1q nephropathy: a variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1232-1240.

doi pubmed - Wenderfer SE, Swinford RD, Braun MC. C1q nephropathy in the pediatric population: pathology and pathogenesis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25(8):1385-1396.

doi pubmed - Wong CS, Fink CA, Baechle J, Harris AA, Staples AO, Brandt JR. C1q nephropathy and minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(4):761-767.

doi pubmed - Hisano S, Fukuma Y, Segawa Y, Niimi K, Kaku Y, Hatae K, Saitoh T, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation and outcome of C1q nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1637-1643.

doi pubmed - Vizjak A, Ferluga D, Rozic M, Hvala A, Lindic J, Levart TK, Jurcic V, et al. Pathology, clinical presentations, and outcomes of C1q nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(11):2237-2244.

doi pubmed - Kersnik Levart T, Kenda RB, Avgustin Cavic M, Ferluga D, Hvala A, Vizjak A. C1Q nephropathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(12):1756-1761.

doi pubmed - Nishida M, Kawakatsu H, Okumura Y, Hamaoka K. C1q nephropathy with asymptomatic urine abnormalities. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(11):1669-1670.

doi pubmed - Muller W, Hanauske-Abel H, Loos M. Biosynthesis of the first component of complement by human and guinea pig peritoneal macrophages: evidence for an independent production of the C1 subunits. J Immunol. 1978;121(4):1578-1584.

pubmed - Lu JH, Teh BK, Wang L, Wang YN, Tan YS, Lai MC, Reid KB. The classical and regulatory functions of C1q in immunity and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2008;5(1):9-21.

doi pubmed - Colvin RB, et al. Glomerular disease. In: Diagnostic pathology kidney diseases 1st ed. Manitoba, Canada: Amirsys Publishing Inc. 2011;84-85.

- Sardani Y, Qin K, Haas M, Aronson AJ, Rosenfield RL. Bartter syndrome complicated by immune complex nephropathy. Case report and literature review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(9):913-918.

doi pubmed - Hanevold C, Mian A, Dalton R. C1q nephropathy in association with Gitelman syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(12):1904-1908.

doi pubmed - Roberti I, Sachdev S, Aronsky A, Kim DU. C1q nephropathy in a child with a chromosome 13 deletion. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(5):737-739.

doi pubmed - Kari JA, Jalalah SM. C1q nephropathy in two young sisters. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23(3):487-490.

doi pubmed - Sharman A, Furness P, Feehally J. Distinguishing C1q nephropathy from lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(6):1420-1426.

doi pubmed - Sinico RA, Radice A, Ikehata M, Giammarresi G, Corace C, Arrigo G, Bollini B, et al. Anti-C1q autoantibodies in lupus nephritis: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1050:193-200.

doi pubmed - Trendelenburg M, Lopez-Trascasa M, Potlukova E, Moll S, Regenass S, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Martinez-Ara J, et al. High prevalence of anti-C1q antibodies in biopsy-proven active lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(11):3115-3121.

doi pubmed - Lau KK, Gaber LW, Delos Santos NM, Wyatt RJ. C1q nephropathy: features at presentation and outcome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(6):744-749.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Nephrology and Urology is published by Elmer Press Inc.